Bringing proven PBS designs to the masses

When the Performance Based Standards (PBS) Scheme was first conceived about 15 years ago, it was thought that one day some PBS trucks would become so abundantly popular that they would be written into the regulations to become as-of-right configurations. In effect, the PBS Scheme would have been the petri dish that spawned them, road-tested them and proved their market value. Writing these PBS designs into the regulations would put them on a level playing field with other as-of-right configurations.

That time has come.

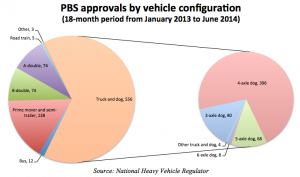

Take a look at the pie chart below. It indicates that about two-thirds of all PBS final approvals are for truck and dog configurations and, of those, about two-thirds are 4-axle dogs. This would suggest that the truck and 4-axle dog is the strongest candidate for writing the first PBS-proven heavy vehicle configuration into the regulations.

Furthermore, many of these approvals are for 19-metre combinations that have been operating legally for years without PBS approval, and only became PBS-approved to gain another five or six tonnes. That’s right, there’s nothing different about the design of these heavy vehicle combinations that makes them all-of-a-sudden worthy of the extra mass; they just happen to fit within a certain general envelope (particularly the height limit) that enables them to meet PBS standards regardless of what suspension and tyre specifications they run. They have enough horsepower to meet the driveline-related standards and they have great swept path performance. So if hordes of these heavy vehicle combinations have been through the PBS approval hoops already, why can’t many times more operate as-of-right provided they look generally the same as those before them?

The questions you might ask are, “How do you put all of the PBS checks and balances around a heavy vehicle configuration that’s written into the regulations? How can you be absolutely certain that a vehicle built to basic mass and dimension regulations will perform according to PBS standards?”

The answer: You don’t.

Remember that a large proportion of existing regulation vehicles DO NOT meet PBS standards. The PBS standards were intentionally set to raise the bar compared with the existing fleet. Think about all of the livestock and logging combinations that wouldn’t satisfy the Static Rollover Threshold requirement. Think about all of the maximum-height woodchip combinations with 3- and 4-axle dog trailers that wouldn’t satisfy the High-Speed Transient Offtracking and Rearward Amplification standards. Think about all of the European cabover trucks with their long front overhangs and big bull bars that wouldn’t satisfy the Frontal Swing standard. The list goes on.

If a non-PBS-compliant vehicle will cause the sky to fall, then we’d better ground a large proportion of the Australian as-of-right fleet. Writing PBS-proven configurations into the regulations should simply be about understanding the risks and managing them.

“If a non-PBS-compliant vehicle will cause the sky to fall, then we’d better ground a large proportion of the Australian as-of-right fleet.”

In the case of truck and dog combinations, they are fairly tightly limited in terms of dimensions. There is a maximum overall length, and minimum axle spacings required to achieve mass. On top of that, there are practicalities that constrain dimensions to be within certain bounds. Height limitation is the main thing, though, with most truck and dogs built low for quarry product transport.

Advantia has proposed a Vehicle Specification Envelope that was presented as one of the options in the National Transport Commission’s recent discussion paper on PBS mass limits for as-of-right truck and dogs. This envelope did not specify any requirements for suspensions and tyres. An assessment of all of the worst-case possibilities of the proposed specification using standard suspension and tyre properties found that they all met PBS standards. If a particular heavy vehicle combination built under the proposed envelope turned out in practice not to meet all of the PBS standards, the risk would be infinitesimal. That’s because when a truck and dog fails to meet PBS standards the extent of the failure (in terms of the vehicle’s additional lateral sway) could probably be measured with a micrometer. Really, 50 mm of additional sway (above the PBS standard of 600 mm) would be considered a big failure.

“When a truck and dog fails to meet PBS standards the extent of the failure (in terms of the vehicle’s additional lateral sway) could probably be measured with a micrometer.”

I’m calling for cool heads during the forthcoming NTC discussions on this issue, and I hope that those within the road authorities who ultimately brief their Council Ministers on the NTC’s recommended arrangements take an apolitical and evidence-based view of the issue, for the good of Australian road freight productivity.

Get more like this in your inbox

Subscribe to our Newsletter and never miss a post.